Аристотель «Поэтика»: Наглядность (1455b22)

Перевод М. Гаспарова

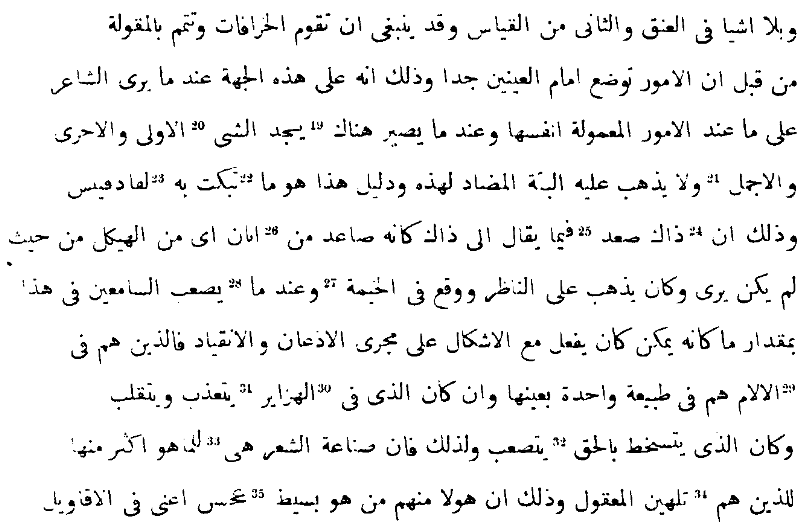

[а22] Складывая сказания и выражая их в словах, следует как можно <живее> представлять их перед глазами: тогда <поэт>, словно сам присутствуя при событиях, увидит их всего яснее и сможет приискать все уместное и никак не упустить никаких противоречий. [а26] Доказательство этому — то, в чем упрекали Каркина: <у него> Амфиарай выходит из храма, но это остается непонятным для зрителя, который не видел, <как он туда входил>, поэтому зрители остались недовольны, и драма провалилась. [а29] Даже жесты должны, сколько возможно, помогать выражению: более всего доверия вызывают те поэты, у которых одна природа в страстях <с выводимыми лицами> — неподдельнее всего волнует тот, кто сам волнуется, и приводит в гнев тот, кто сам сердится. [а32] Поэтому поэзия — удел человека или одаренного, или одержимого: первые способны к <душевной> гибкости, а вторые к исступлению.

Перевод В. Аппельрота

Перевод Н. Новосадского

По возможности следует сопровождать работу и телодвижениями. Увлекательнее всего те поэты, которые переживают чувства того же характера. Волнует тот, кто сам волнуется, и вызывает гнев тот, кто действительно сердится. Вследствие этого поэзия составляет удел или богато одаренного природой, или склонного к помешательству человека. Первые способны перевоплощаться, вторые — приходить в экстаз.

Translated by W.H. Fyfe

Translated by S.H. Butcher

Again, the poet should work out his play, to the best of his power, with appropriate gestures; for those who feel emotion are most convincing through natural sympathy with the characters they represent; and one who is agitated storms, one who is angry rages, with the most lifelike reality. Hence poetry implies either a happy gift of nature or a strain of madness. In the one case a man can take the mould of any character; in the other, he is lifted out of his proper self.

Translated by I. Bywater

Traduction Ch. Emile Ruelle

II. La preuve en est dans ce que l’on reprochait à Carcinus. Amphiaraüs était remonté du temple sans que le spectateur pût le voir; et, à la scène, la pièce échoua, par suite du mécontentement que cette faute causa aux spectateurs.

III. Il faut mettre autant de faits qu’on le peut en rapport avec les rôles, car, en vertu de la nature même, les personnages les plus persuasifs sont ceux qui éprouvent les passions qu’ils font paraître. On provoque l’agitation quand on est agité