Аристотель «Поэтика»: Объем трагедии (1450b43)

Перевод М. Гаспарова

Перевод В. Аппельрота

Перевод Н. Новосадского

Translated by W.H. Fyfe

The limit of length considered in relation to competitions and production before an audience does not concern this treatise. Had it been the rule to produce a hundred tragedies, the performance would have been regulated by the water clock, as it is said they did once in other days. But as for the natural limit of the action, the longer the better as far as magnitude goes, provided it can all be grasped at once. To give a simple definition: the magnitude which admits of a change from bad fortune to good or from good fortune to bad, in a sequence of events which follow one another either inevitably or according to probability, that is the proper limit.

Translated by S.H. Butcher

Translated by I. Bywater

Just in the same way, then, as a beautiful whole made up of parts, or a beautiful living creature, must be of some size, a size to be taken in by the eye, so a story or Plot must be of some length, but of a length to be taken in by the memory. As for the limit of its length, so far as that is relative to public performances and spectators, it does not fall within the theory of poetry. If they had to perform a hundred tragedies, they would be timed by

Traduction Ch. Emile Ruelle

IV. Il ne faut donc, pour que les fables soient bien constituées, ni qu’elles commencent avec n’importe quel point de départ, ni qu’elles finissent n’importe où, mais qu’elles fassent usage des formes précitées.

V. De plus, comme le beau, que ce soit un être animé ou un fait quelconque, se compose de certains éléments, il faut non seulement que ces éléments soient mis en ordre, mais encore qu’ils ne comportent pas n’importe quelle étendue; car le beau suppose certaines conditions d’étendue et d’ordonnance. Aussi un animal ne serait pas beau s’il était tout à fait petit, parce que la vue est confuse lorsqu’elle s’exerce dans un temps presque inappréciable; pas davantage s’il était énormément grand, car, dans ce cas, la vue ne peut embrasser l’ensemble, et la perception de l’un et du tout échappe à notre vue. C’est ce qui arriverait, par exemple, en présence d’un animal d’une grandeur de dix mille stades.

VI. Ainsi donc, de même que, pour les corps et pour les êtres animés, il faut tenir compte de l’étendue et la rendre facile à saisir, de même, pour les fables, il faut tenir compte de la longueur et la rendre facile à retenir.

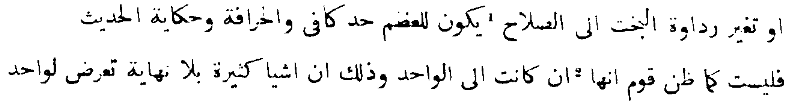

VII. Quant à la délimitation de la longueur, elle a pour mesure la durée des représentations, et c’est une affaire d’appréciation qui n’est pas du ressort de l’art; en effet, s’il fallait représenter cent tragédies, on les représenterait à la clepsydre, comme on l’a fait,

VIII. C’est la nature

IX. Du reste, pour donner une détermination absolue, je dirai que, si c’est dans une étendue conforme à la vraisemblance ou à la nécessité que l’action se pour suit et qu’il arrive successivement des événements malheureux, puis heureux, ou heureux puis malheureux, il y a juste délimitation de l’étendue.