Аристотель «Поэтика»: Как вызывать сострадание и страх (1453b1)

Перевод М. Гаспарова

Перевод В. Аппельрота

Перевод Н. Новосадского

Translated by W.H. Fyfe

Translated by S.H. Butcher

Translated by I. Bywater

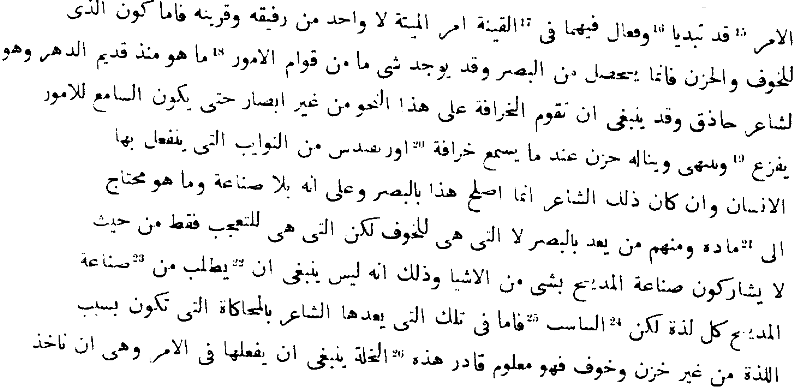

The tragic pleasure is that of pity and fear, and the poet has to produce it by a work of imitation; it is clear, therefore, that the causes should be included in the incidents of his story.

Traduction Ch. Emile Ruelle

II. En effet, il faut, sans frapper la vue, constituer la fable de telle façon que, au récit des faits qui s’accomplissent, l’auditeur soit saisi de terreur ou de pitié par suite des événements; c’est ce que l’on éprouvera en écoutant la fable d’Oedipe.

III. La recherche de cet effet au moyen de la vue est moins artistique et entraînera de plus grands frais de mise en scène.

IV. Quant à produire non des effets terribles au moyen de la vue, mais seulement des effets prodigieux, cela n’a plus rien de commun avec la tragédie, car il ne faut pas chercher, dans la tragédies, à provoquer un intérêt quelconque, mais celui qui lui appartient en propre.

V. Comme le poète (tragique) doit exciter, au moyen de l’imitation, un intérêt puisé dans la pitié ou la terreur, il est évident que ce sont les faits qu’il doit mettre en oeuvre.